Updated on January 6, 2022, to fix a not-helpful correction by the spell checker.

Hello from FedInvent,

Happy 2022.

Our weekly patent analysis got started a little late this week. USPTO dropped this week’s patents a little late.

We had our first snow of any significance in three years. The area was mesmerized watching the drone photographs of all the cars and trucks stuck on I-95 in Northern Virginia, we couldn't help but wonder how the Virginia Department of Transportation would refuel vehicles if all the vehicles on the road were electric? How would all those batteries that lose up to 20% of their range in cold weather handle keeping passengers warm in freezing temperatures? How would VDOT deal with miles of dead EVs needing a charge? Note to DOT and DOE, another area ripe for federally funded research is how to provide mobile recharging capabilities in emergencies.

Today we took a little detour and write about a uniquely federal aspect of the innovation ecosphere, the federal patent conundrum.

The Federal Patent Conundrum

The patent conundrum is simple. How do you accelerate getting important taxpayer-funded innovations to the marketplace when you don't make things?

The federal innovation ecosphere faces unique challenges getting inventions to the marketplace. Most of the recipients of taxpayer-funded patents rely on others to commercialize their patented technology. Universities, federally funded research and development centers, DOD's university-affiliated research centers, and federal departments and agencies don't build things. They license things. (We'll save the discussion on the lack of transparency on licensing taxpayer-funded patents for another day.)

In fast-moving areas of science and technology like cybersecurity, biomedical devices, artificial intelligence, mobile applications, the internet of things, and anything software or business methods-driven, the government has a vested interest in getting these discoveries to the market fast — economic reasons, American competitiveness reasons, environmental reasons, national security and defense reasons. Taxpayer-funded patents pose an interesting conundrum. How do the organizations that pay for important, policy-driven inventions complete the trip from idea to the marketplace?

Here are two examples of the federal patent conundrum from the fast-moving world of national security technology. The National Security Agency (NSA) may find itself inhibited in deploying new cybersecurity innovations by the very patents it paid for. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Transportation Safety Administration (TSA) are busy trying to hoover up a crop of identity management inventions, so it doesn't have to worry that the private sector patents will prevent it from implementing the technology TSA prefers.

NSA's Cybersecurity Innovations

The National Security Agency has become more public about its efforts to improve the cybersecurity of US critical infrastructure and help secure US companies that own important national security-related technology. Most of what the NSA does is usually hidden behind the walls of Fort Meade. The NSA Research Directorate sponsors a public Science of Security (SOS) Initiative to promote foundational cybersecurity science needed to mature the cybersecurity discipline and underpin advances in cyber defense. NSA partnered with a group of top cybersecurity researchers in academia. The SOS Lablets are Carnegie Mellon University, Vanderbilt University, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, North Carolina State University, the International Computer Science Institute, University of California, Berkeley, Kansas University, and the University of Alabama. These entities, in turn, expanded the research infrastructure to a group of Associate Lablets. This brings the count to over 20 universities participating in the SOS research infrastructure.

The SOS Lablet program seeks to solve fundamental security problems:

Resilient Architectures — How do you build resilient systems that can continue to work when security is compromised.

Secure Collaboration — Secure collaboration is focused on what happens to security when information is moving between devices and platforms.

Metrics — How do cybersecurity people meet the challenge of measuring how secure something is. (Current federal cybersecurity programs haven't met this challenge yet. Sorry NIST and FedRAMP.)

Scalability and Composability — Cybersecurity solutions work when they are small but not always when the systems get big. (Solving this problem is essential for enabling secure use of DevSecOps continuous development and continuous integration, the composable part of the equation. How do you build a secure system when they are changing all the time?)

Human Behavior of Cybersecurity — How do humans interact with systems and make decisions on how to use them. Human behavior is the field of cybersecurity that deals with technology that wasn't prepared for humans.

The goal of the SOS program is to create pubic, unclassified research to accelerate the introduction of essential security features into products that the federal government could acquire. These same capabilities should, in turn, spread into the private cybersecurity marketplace. Then patents showed up.

There is a new realization within the federal cybersecurity research community that patents slow down the dispersion of the innovation into marketable products and critical infrastructure. NSA's mission is to build and deploy state-of-the-art technology to meet the government's urgent need to protect national security. It partnered with experts. The experts are pros at filing for patents. NSA now has to wait for the patent applicants to commercialize the technology it paid for. NSA may have certain rights to the innovations, and it may be in a position to be able to deploy them internally. It will have to wait to work with critical infrastructure providers and purveyors of national security technology to deploy its R&D in those environments. Its quest for buyable and deployable technology depends on a third party. The hackers move at the speed of the internet and aren't concerned about patents (or getting a CISSP, for that matter.) NSA may find itself inhibited in deploying new cybersecurity innovations by the very patents it paid for while the hackers invade our infrastructure.

(You can listen to an interview with Adam Tagert, an NSA SOS Researcher, where he discusses the patent issue briefly.)

DHS Patent Monopoly And The Mobile Duopoly

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is a significant decision-maker and regulator in the identity management and biometrics space with veto and endorsement authority that drives what technology is selected for deployment in the global travel security world.

The biggest driver of identity management technology is Transportation Safety Administration (TSA). Even during the Omicron outbreak, TSA hits almost 1.8 checkpoint encounters with travelers a day. Congress wants TSA to shorten wait times. Mobile solutions to streamline security are high on TSA's priority list.

The DHS intellectual property program is antithetical to NSAs. Its approach is to try to beat the private sector to the Patent Office with "a proactive patent strategy to ensure that no vendors file patents that could negatively impact TSA's ability to choose the best solution for identity verification." DHS has been busy trying to get patents in the mobile identity space. Its patent monopoly exploits will need to rely on the mobile operating system duopoly and intellectual property virtuosos Apple and Google if they want to get their preferred and patented identity technology onto travelers' smartphones. The DHS and TSA patent gambit is more than a little problematic.

DHS funds and participates in the standards working groups that lead to global standards for identity management — Real ID, mobile driver's license (mDL), and biometrics. It makes the rules on how identity programs work -- TSA PreCheck and CLEAR, its only commercial competitor so far. DHS drives decisions on what critical identity technology will be used by the global travel industry is.

This role gives the DHS and TSA outsized influence on how the standards evolve and what technical requirements make it into them. The program managers responsible for deploying the standard-compliant mobile solutions and publicly pitching the TSA agenda to the public are filing patent applications and getting patents on the technology they can't commercialize themselves. (Maybe they'll try.)

DHS also casts a big net. TSA employees show up as inventors on patents owned by Apple for checkpoint identity verification. Some of the same DHS inventors appear on mobile identity management patent applications that touch a broad set of uses beyond TSA's transportation safety mission. These applications cover voting, electronic health records, merchant and personal transactions, and wayfinding identity applications for mass transit, border security, correctional facilities, department of motor vehicles, sporting events, testing centers. Patent attorneys from TSA are the inventors on a new internet of things (IoT) lock and identity management patent for replacing the worthless dual-key physical locks for checked baggage.

So DHS and its TSA employee inventors get a patent giving them a monopoly that relies on the smartphone operating system duopoly. Now what? Do they go on a licensing road trip to get the mobile and identity industry to license their technology? Do they offer FRAND licenses? Do they hire a contractor to build the app? Do they offer exclusive licenses? (Given the recent Apple/DHS announcements, it feels like TSA is leaning Apple at the moment.) It's complicated.

Two Approaches, Same Conundrum

NSA and DHS face the same conundrum. They have policy imperatives to develop transformational technology with urgency to deploy it. Both use taxpayer funding to pay for seminal research or industry standards to solve compelling problems. Both agencies must rely on third parties to commercialize the inventions. At the risk of sounding anti-patent, we're not, it may be time for more creative thinking on better solutions for the taxpayer-funded patent conundrum.

A FEW NOTES:

There is no easily obtainable timely information on a federal department's licensing success rate. We have some indicia of when a patent owned by a university is licensed, but the same problem exists for those patents.

Because a lot of the information on the standards working group responsible for the mDL standard is confidential, we don't know whether DHS disclosed its patenting activity during the process.

We still have questions on how a patent that started with DHS inventors and DHS as the assignee when the application was published wound up with Apple inventors and DHS personnel as inventors by the time the patent was granted. Apple is now the assignee on the patent. We're working on it. (You can read the earlier newsletter here.)

On to this week's patents.

Patents By The Numbers

Here are the links to the Tuesday FedInvent Patent Report and to the Details Page that lets you browse by department.

This week USPTO granted 6,809 new patents. One hundred sixteen (116) benefitted from taxpayer funding. Here are the numbers.

One hundred fifteen (115) patents have Government Interest Statements.

Nineteen (19) have an applicant or an assignee that is a government agency.

The 116 new patents have 141 department-level funding citations.

These patents are the work of 436 inventors.

The 418 American inventors come from 37 states and the District of Columbia.

The Big Three States:

California has 22 first-named inventors and 78 total inventors. Massachusetts has 12 first-named inventors and 54 total inventors.

Florida has nine (9) first-named inventors and 28 total inventors.

The eighteen (18) foreign inventors come from 11 countries.

There are 80 patents (69%) where at least one assignee is a college or university, the HERD.

Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) received seven (7) patents.

A federal department is the sole assignee on nine (9) patents.

Nine patents have Y CPC symbols indicating that USPTO believes these inventions may be useful in mitigating the impact of climate change. The Patent Office appears to be assigning Y02 classifications indicating technology useful in adapting to climate change to cancer treatments. We haven't seen much research indicating that cancer and climate change are linked. The rules for the assignment of these Y symbols remain a mystery.

There are no Bayh-Dole scofflaws this week. (An excellent way to start the new year.)

Patent Count By Department

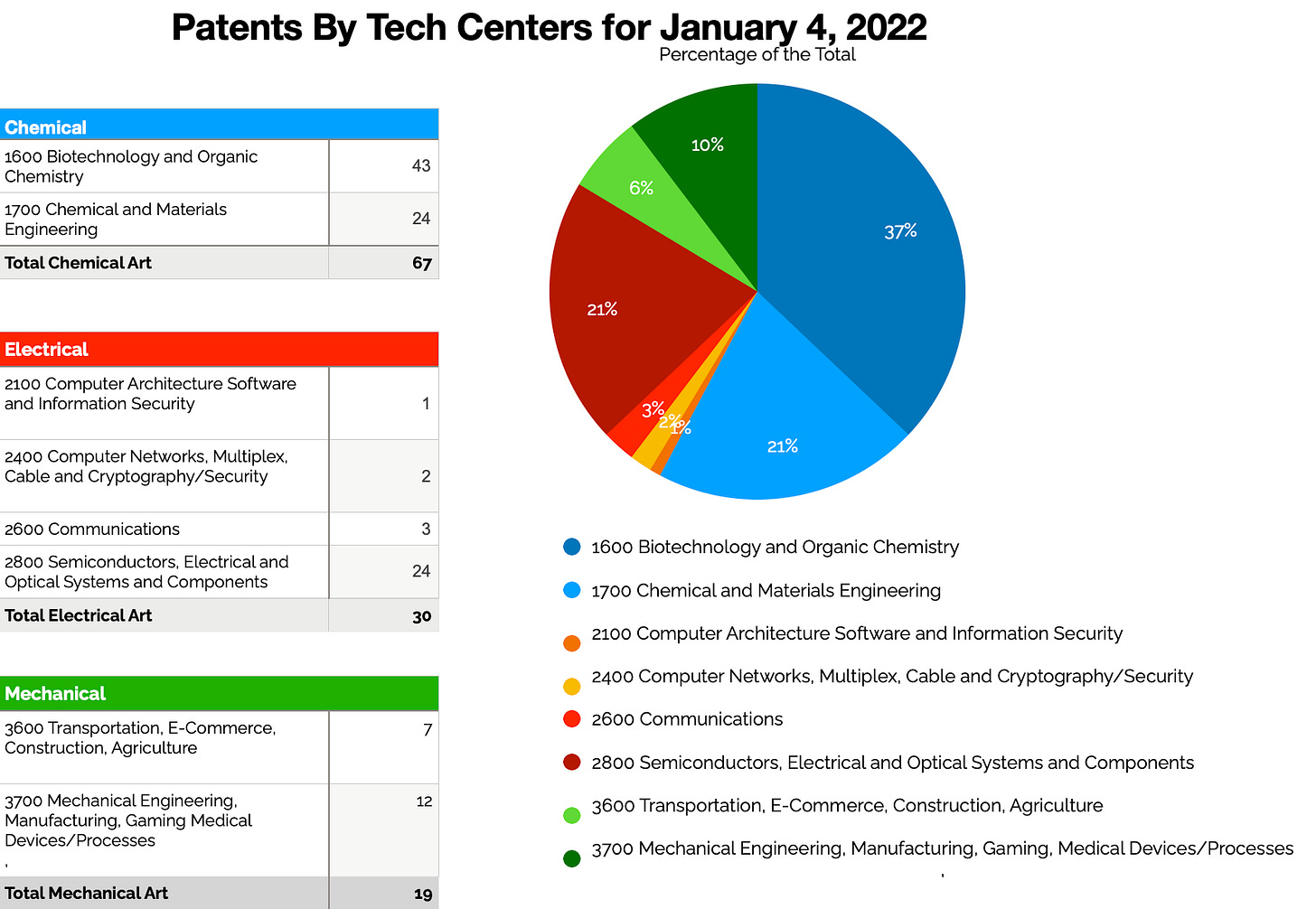

Patents By Technology Center

The Technology Centers where the 116 patents granted this week were examined are in the chart below.

The Health Complex

The table below shows the number of funding citations where the recipient cites the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the institutes at the National Institutes of Health, and other subagencies that are part of HHS, the Health Complex.

Before We Go

This year FedInvent is working on adding year-to-date counts to the FedInvent Reports. Please stay tuned.

As usual, there are many more taxpayer-funded patents than we can cover here. Please explore the FedInvent Patent Report. It's an important addition to your newsletter subscription.

If you'd like to catch up on earlier FedInvent Reports, you can access the newsletters here on Substack. In addition, the reports are available on the FedInvent Links page.

If you aren't a paid subscriber yet, please consider subscribing. It will help us keep going in 2022.

As always, we thank you for reading FedInvent.

The FedInvent Team

FedInvent tells the stories of inventors, investigators, and innovators.

Wayfinder Digital's FedInvent Project follows the federal innovation ecosphere, taxpayer money, and the inventions it pays for. FedInvent is a work in progress. Please reach out if you have questions or suggestions. You can reach us at info@wayfinder.digital.