Hello from FedInvent,

It is an interesting time in the innovation ecosphere.

On Sunday, The New York Times published an editorial called Save America's Patent System. (You can read it here if the paywall doesn't interfere.). The editors of the NY Times, a publication that never publishes a patent number or adds a link to a patent in an article discussing a patent, highlighted the not new, definitely obvious, and not so useful ways the patent system works.

The editorial highlights drug makers' use of incremental improvements to their patented drugs to keep their drugs and revenue streams going forever — it's a shot, a pill, and a capsule. The editorial board notes that the patent system is the domain of insiders who only know how to speak to members of the patent tribe.

One of the NY Times editorial recommendations is that the patent system needs to let the public participate. The editorial notes that the public doesn't understand how patents impact both marketplaces where they buy goods and services and public policy decision-making.

Take the "March-In Rights" discussion, for example. Drug prices are too high. The federal government funded the original research that led to the discovery of the blockbuster new drug. The public shouldn't have to pay this much. The inventors who received money got a patent on their discovery. The patent owner, usually a university, licenses the patent to a drug company that commercializes the invention. The university and the inventors earn big-time royalties if the drug is a success.

Commercializing isn't just putting a price tag on it. The drug company charges a lot of money for the drug because it costs them a bundle to take a patented compound and turn it into a drug approved by the FDA. Drug companies like to make money because they have to pay for things too.

There's a financial rubric afoot for the drugs that resulted from these patented inventions. The rubric works something like this. Treating a particular life-threatening disease costs, say, $1 million over the patient's life. The drug company with the blockbuster drug can now cure the disease. They charge the patient $250,000 for the treatment because the insurance companies or Medicare will foot the bill. The justification for the high prices is that the drug can cure the disease for $250,000. The patient can continue to use the old treatments that the insurance company will pay for and spend $1 million, not adjusted for inflation. That sounds like a deal. Maybe, maybe not. The public needs more information on how the drug supply chain operates and how intellectual property-based companies create and use their patents.

(Don't get me started on drugs to treat mental health disorders that cost $6,000 a month but lead to tardive dyskinesia. To help control tardive dyskinesia, you need another drug that can add another $6,000 to $7,000 a month to the drug bill. Without patient assistance from the drug companies, most (all) people with serious mental health diagnoses can't afford $12,000 a month for drugs on a $1,300 a month social security disability check.)

Lots of Lawyers

The current answer to high drug prices? The government should march in and take the patents and license them to other companies who will make another version of the drug and sell it for cheap. Problem solved. Well, not really.

It's unclear how the federal government could pull off a march-in. They've never done it before. There is no precedent. Patients will still be paying a lot of money for the drugs while the march-in battle rages and the new drug maker spins up their manufacturing. The march-in will be an epic payday for patent and drug industry lawyers. Getting this process through the courts could take years. The new drug company that is the recipient of the patent the government marched in can expect their own legal issues, a flood of lawsuits, and restraining orders. A march-in is for lawyers, not for patients. This drug pricing situation calls for a more creative solution than years in court.

Unclog the Clogged Pipeline

The NY Times points out that the patent system is clogged up with patent applications from inventors that resubmit rejected patent applications over and over again. The Times doesn't point out that some of this relentless resubmission is deliberate.

Start-ups raising money want a slide in the pitch deck that says, "We're patent pending." It's a sophisticated take on "fake it til you make it" culture. The logic is that patents are hard. If this start-up is patent pending, they must be on to something novel, useful, and non-obvious—patent pending status ups the odds of raising money.

We work with the founders of start-ups with new and emerging technology. After signing the non-disclosure agreement and making sure the retainer check didn't bounce, we ask the founders, "if they think you're going to get a patent on this invention?" The response is usually something like, "No, but it gives me three or four years to tell everyone that my product is patent pending. It buys us time to raise money and build marketshare."

Most start-ups with patent applications are small, so they qualify as micro-entities. The fees are low, so it's cheap to keep requesting reexamination. The current process allows these founders to milk the timeline. If you have six months to respond to a rejection office action, why respond early? Keep that patent application percolating to keep the patent pending line in the pitch deck.

Patent examiners need to be able to call fouls on some of these patent applications. They should at least have some tools to get this stuff off their docket faster — higher fees, shorter office action response time for the second and third requests to reconsider their rejection, to name a few. USPTO needs to figure out how to stop letting these IP gamers drag out a process that holds up other patents from getting to a patent examiner.

Take More Time But Get It Done Faster

Patent examiners only spend about 19 hours examining a patent application. That's not enough. But, if you give examiners more time, you're going to need more examiners, or you're going to watch the pendency time lengthen again. The examiners need more time. Their constituents want faster decisions. This is a challenge.

Speed Up Drug Discovery

Sunday Review section of the Times also had another essay on the pharmaceutical industry. The essay "A Deadly Delay in COVID Drugs," was written by Bill Gates. Mr. Gates supports the use of technology such as gene sequencing, protein hunting, 3D modeling and robots that can run thousands of tests, and "On-A-Chip" devices that mimic how human organs work to enable researchers to see how different compounds work to speed up drug discovery. (We love a good "on-a-chip" invention.) All of these technologies are patented, too.

Mr. Gates knows a lot about patents and how to use them in the marketplace. Mr. Gate's essay doesn't mention the words patents or intellectual property once. A patent guru wanting to speed up drug delivery didn't cite the patent system as an impediment to innovation. Cognitive dissonance has set in.

(You can read about Microsoft's patent journey in "Burning the Ships, Intellectual Property and the Transformation of Microsoft" by Marshall Phelps and David Kline.)

Taxpayer-Funded Patents

We started FedInvent to make it easier for people to understand what their taxpayer dollars pay for. We report on who is inventing and patenting new inventions. We publish FedInvent so our readers can decide if they are getting a good return on their investment.

Most of the patents in the drug pricing Bayh-Dole march-in discussions started as invention disclosures and patent applications based on R&D funded by the government. Many inventions come from the government's call to the scientific community to help them solve daunting problems.

Unlike private-sector patents, federally funded patents provide a path to the information on how the invention came to be. Where else can you track a patent back to the researcher's grant application that explains what they are researching, why it matters, how much they think it will cost to solve a problem, and where the invention fits in the innovation ecosphere?

If you want to know which government agencies are funding and building technology to track geopolitical events on social media, read the patents and follow DARPA, DOD, and the intelligence community. If you want to know which FFRDC is figuring out how to use 3D printing at scale, read the patents from researchers at Oak Ridge National Lab and the University of Tennessee. If you want to know about the latest developments in quantum computing, read the patents. You'll have to guess who funded them, but it's safe to say the National Security Agency and DOD. If you want to know who will have the best, most sophisticated augmented and virtual reality and avatars that look like real people, read the University of Southern California patents and watch the university spinouts that received Small Business Innovative Research grants. Even if the inventions never make it to the marketplace, where else can you track an invention back to the science and technology public policy that set it in motion?

An Intellectual Property Machine

So far this year, there is an average of 130 new taxpayer-funded patents and 167 patent applications published each week. If the government was a corporation getting 130 new patents and having 167 new patent applications published each week, the business media and innovation economists would pay more attention to what is coming from the federal intellectual property machine.

Bayh-Dole Scofflaws

There are three Bayh-Dole scofflaws — General Electric, Johns Hopkins, and Raytheon. The Johns Hopkins patent application is signed by the Chief of Staff for the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab. The Applied Physics Lab is a Department of the Navy FFRDC and University Affiliated Research Center. We'll add this to the DOD list of patent applications. The General Electric and Raytheon patents relate to gas turbine engine technology. This week's Bayh-Dole scofflaws are all defense contractors.

The USPTO finally has a new director, Kathi Vidal, a Silicon Valley patent attorney. Ms. Vidal was confirmed by the Senate and sworn in on April 13, 2022. The official USPTO press release says, "Director Vidal began her career as a systems and software design engineer with General Electric and Lockheed Martin, where she designed one of the first artificial intelligence systems for aircraft, as well as aircraft and engine-control systems that continue to keep our military safe today." A USPTO director who understands defense contractors. Maybe she can do something about the Bayh-Dole scofflaws.

Patent Applications By the Numbers

Here is the link to the FedInvent Report for patent applications granted on April 14, 2022. If you prefer to browse by department, start here.

On April 14, 2022, the US Patent Office published 6,906 pre-grant patent applications, 147 benefitted from taxpayer funding. Here is how things broke down on Thursday.

One hundred forty-three (143) patent applications have Government Interest Statements.

Twenty-three (23) applications have an applicant or an assignee that is a government agency.

A federal department is the only assignee on ten patent applications.

The 147 new patent applications have 167 department-level funding citations.

These applications are the work of 516 inventors.

The 504 American inventors come from 40 states and the District of Columbia.

The twelve foreign inventors come from six (6) countries.

This week there are three inventors from China.

There are 94 patent applications (64%) where at least one assignee is a college or university, the HERD.

Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) have 16 published patent applications. Four other patent applications were funded by an FFRDC. (The count is 17 if our research on the Bayh-Dole scofflaw is correct.)

There are four patent applications with a Y CPC symbol indicating that the invention may be useful in mitigating the impact of climate change.

The Big Three

This week's top three states are:

California had 24 first-named inventors and 87 total inventors.

Massachusetts had 18 first-named inventors and 51 total inventors.

Texas had ten (10) first-named inventors and 23 total inventors.

The 161 American inventors from these three states account for 32% of the inventors on the week's published patent applications.

Count By Department

This week DOD moved out of its Number Two position with NSF moving up. This week DOE and DOD tied for third place.

Health Complex Year To Date

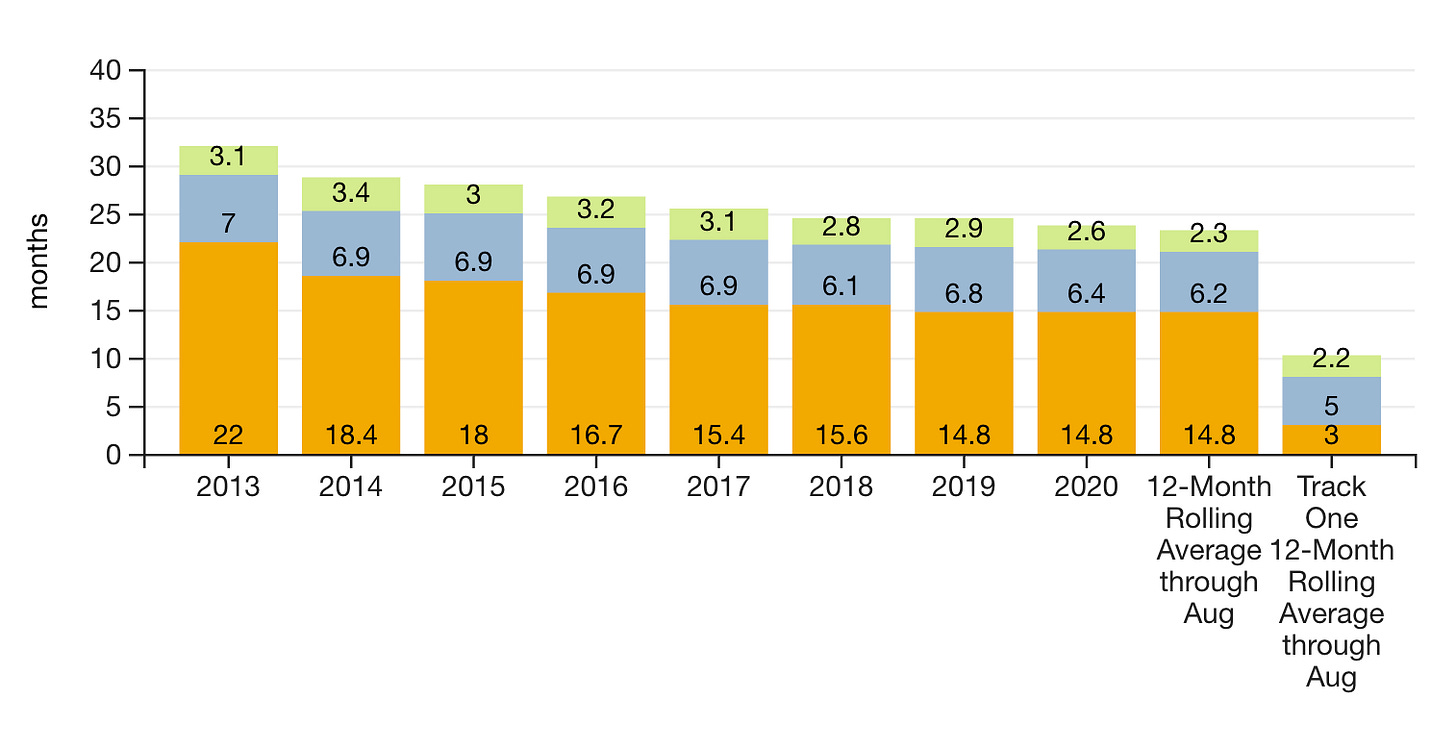

The Health Complex's inventors have included individual funding citations on the pre-grant patent applications published since the beginning of 2022. You can see the details here. This week's Bar Chart is here.

We update our Messages from Ukraine page with the latest news. We finally received an update.

Thank you for reading FedInvent.

The FedInvent Team

FedInvent tells the stories of inventors, investigators, and innovators. Wayfinder Digital's FedInvent Project follows the federal innovation ecosphere and taxpayer-funded inventions. FedInvent is a work in progress. Please reach out if you have questions or suggestions. You can reach us at info@wayfinder.digital.