Updated May 24, 2022

Hello from FedInvent,

First, we want to catch up on getting you the links to the FedInvent Reports.

FedInvent Report for Taxpayer-Funded Patent Applications, published on May 12, 2022, is here. The link to the detail page for department-level browsing is here.

FedInvent Report for Taxpayer-Funded Patents granted on May 17, 2022, is here. The link to the detail page for department-level browsing is here.

FedInvent Report for Taxpayer-Funded Patent Applications, published on May 19, 2022, is here. The link to the detail page for department-level browsing is here.

This week the Health Complex — the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the institutes at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) hit new milestones. HHS has received 1,012 patents so far this year. NIH has 962 where it was cited by inventors as the source of research and development funding. Health Complex citations for unique funding sources cited by the inventors on the 1,012 patents totaled 3,242. (Institute and agency counts are here.)

The Department of Defense (DOD) 2022 year-to-date count reached 720 patents on May 17th. If you add in the Bayh-Dole scofflaws, mostly defense contractors, and the patents for the DOD-related Intelligence Community, the DOD patent total this year is 776, give or take a few scofflaw patents.

The Mix

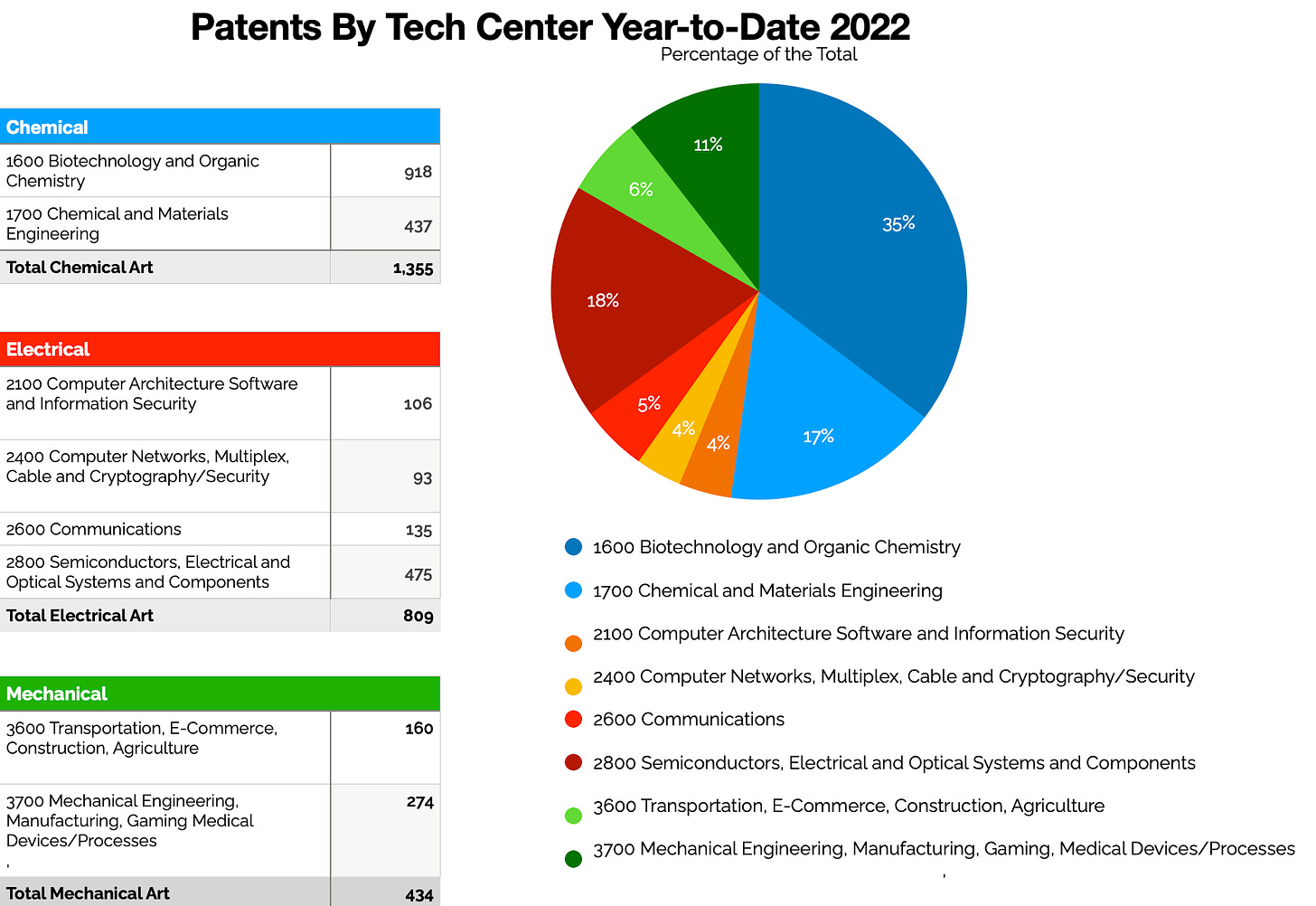

The Technology Center mix for taxpayer-funded patents remains consistent.

Giant Monsters

The Air Force has a flair for naming its programs after space movies and other cultural memes. There is Kobayashi Maru, and Kessel Run.

The Kobayashi Maru program is named after the Kobayashi Maru simulation, a supposedly unwinnable scenario in the Star Trek universe. Kobayashi Maru was finally beaten when Captain Kirk hacked the system. (Hacker's delight.) The Space Command and Control (C2) program (Kobayashi Maru) provides capabilities that bring critical services to our warfighters to facilitate timely, quality battlespace decisions.

Kessel Run is named for Star Wars and Han Solo and his spacecraft, the Millennium Falcon. The Kessel Run was a 20-parsec route used by smugglers to move glitterstim spice from Kessel to an area south of the Si'Klaata Cluster without getting caught by the Imperial ships that were guarding the movement of spice from Kessel's mines. The Millennium Falcon's maximum speed is 652 mph. It made the Kessel Run in 12 parsecs. The F-35C can reach speeds of 1.6 Mach (~1,200 mph) even with a full internal weapons load. It looks like the USAF can make the run in 6 parsecs.

Kessel Run is the operational name for the work of Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) 's Detachment 12. Kessel Run's mission is to deliver combat capabilities warfighters love and revolutionize the Air Force software acquisition process. Kessel Run builds, tests, delivers, operates, and maintains cloud-based infrastructure and warfighting software applications for Airmen worldwide.

This week, giant monsters are making an appearance. The Air Force published solicitation FA8650-22-S-1004, Air Force Program is Kaiju.

Kaiju's goal is to deliver research, develop and transition advanced electronic warfare technologies to ensure future dominance of the US and its allied nations within the electronic warfare electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) across all domains. These advanced EW technologies will encompass the following technical areas:

Data collection,

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML),

Modeling and simulation,

Algorithm design and development,

Hardware development,

Testing (in the lab and the field), and

Analysis.

(A panacea of new and emerging technology.)

Kaiju is a Japanese genre of films and television featuring giant monsters. (We love a good giant monster movie. )The term kaiju refers to the giant monsters themselves. The monsters are usually depicted attacking big cities and battling the military or other monsters. The first appearance of a notable Kaiju was in the 1933 film King Kong by RKO Pictures. Kaiju vs. Kaiju first appeared in the 1962 Godzilla film King Kong vs. Godzilla. Two Kaiju in one movie.

The Air Force expects to award up to eight contracts through the Kaiju program and estimates the value of individual awards will range between $1 million and $95 million. (Serious money.) Kaiju is an applied research program. FedInvent will be watching to see who wins the contracts and what new intellectual property comes from the program.

(We wondered if King Kong would make an appearance to audition for the Air Force program logo. Unfortunately, he was a no-show. But we got some good pictures of the Empire State Building.)

The Innovation Equation

The FedInvent innovation equation goes like this. The federal government identifies science and technology needs and sets policies. Next, the R&D intense agencies craft broad agency announcements advertising their R&D priorities and invite proposals from the US science and technology community. The agencies fund grants and contracts. Innovators innovate and apply for patents. USPTO grants patents, and if everything works out, the inventions make their way to the marketplace and create economic growth, usually with a host of regulatory and statutory product issues that need to be addressed along the way.

There is an inverse to this equation. The federal government needs innovative technology to help meet the need for new capabilities to meet mission objectives. So the agencies do market studies. Government personnel go to trade shows on the hunt for cool technology. Then agencies evaluate technology, put out requests for proposals, and await innovative solutions from American companies large and small, mostly large. Sometimes the agencies get what they are looking for—a lot of times they don't.

Selling to the federal government is rugged for many businesses delivering new and innovative products. Just reading through an RFP can be daunting. Small companies and start-ups routinely weigh the bandwidth needed to deal with the nuances of government proposals and the long list of compliance requirements that go with winning a government contract award. Many times they decide bidding is just not worth the effort.

DOD and military branch leadership have expressed urgency on the need to engage more companies to work with them to help solve some of the most pressing national security challenges. But attracting small businesses to work with them is elusive at best. Last week the Department of Defense (DOD) threw another wrench into its efforts to get small innovative companies to work with it. DOD set up yet another barrier to entry for some of the country's most innovative companies.

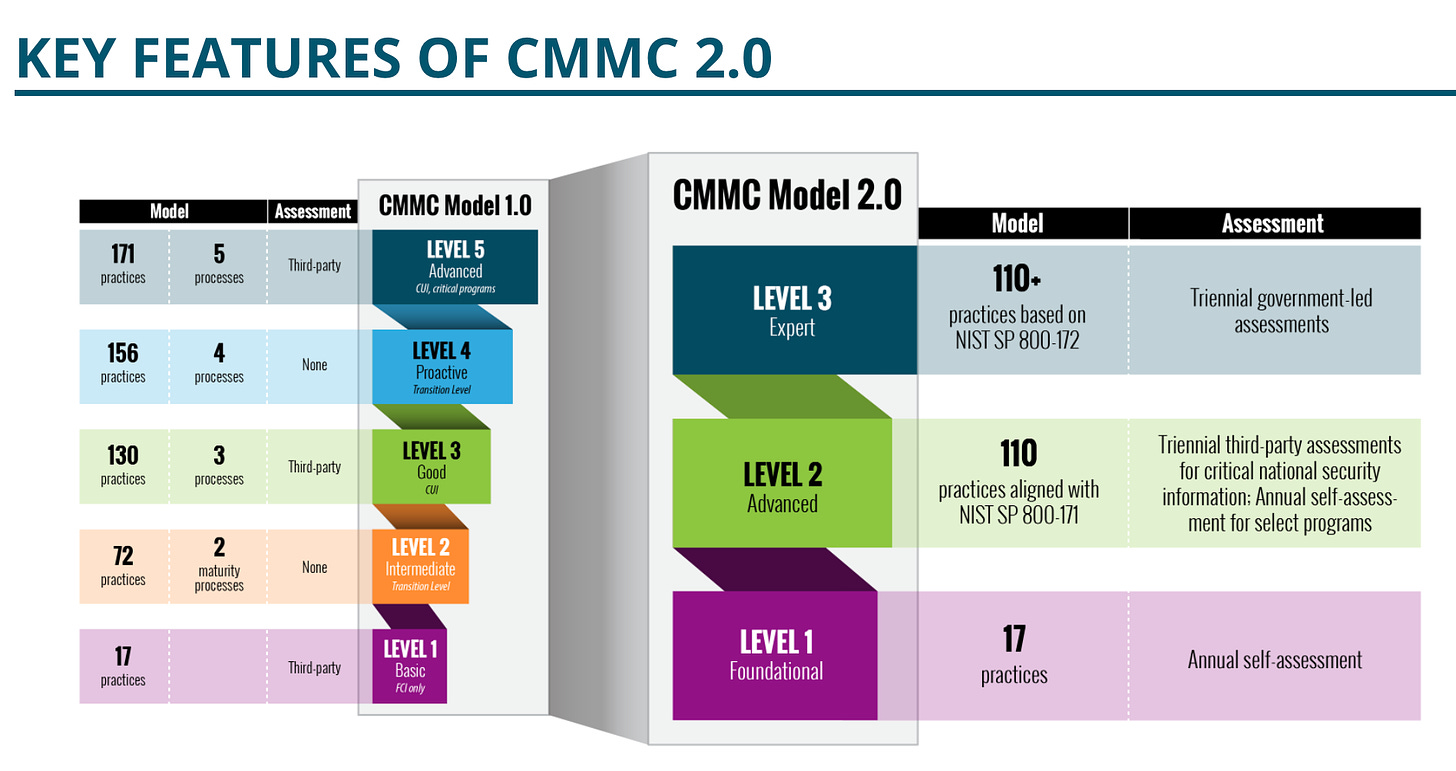

DOD is rolling out the latest version of its Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC), its program to improve the cybersecurity capabilities of the defense industrial base. The CMMC program will become part of the federal contract requirements for new acquisitions starting in May 2023. CMMC is based on the National Institute of Standards and Technology's 800-171 standard, a standard for government contractors handling controlled unclassified government information (CUI). It is a comprehensive set of cybersecurity controls designed to meet the government's needs.

DOD's latest promotional material promises that CMMC 2.0 cuts red tape for small and medium-sized businesses. It doesn't look that way to us. So we decided to double-check if our read was correct. When we asked the cybersecurity companies that provide the professional services to help their clients become CMMC compliant, they gave us this breakdown of the path to compliance:

Start with policies and documentation. Most small and medium-size companies don't have the policy and operational documentation needed to be compliant — access control policies, risk assessment policies, and physical security policies, to name a few. Nor do they have the artifacts and lists needed to support these policies. Developing the documentation usually takes four to six months.

An initial Readiness Assessment that analyzes where a firm's cybersecurity technology stands can cost up to $80,000. Seems like a lot? The $80,000 cost covers two cybersecurity engineers at an average hourly rate of $250 for two months. For a vendor with a mature cybersecurity program cybersecurity the assessment can take as little as three weeks, but that's not the norm.

Continuing compliance requires the acquisition of technology to support continuous monitoring and vulnerability management. Depending on the company's technology, these tools can cost another $125,000 to acquire and set up. The tools may not exist for some of the newest technology — sensors, wearables, and mobile devices. (More innovative technology for the government to buy.)

Certified third-party auditors who assess a vendor's cybersecurity plan may cost $20,000-$40,000. The third-party assessor organizations we've worked with tell a different story. The costs for a CMMC assessment are closer to $125,000-$300,000. The higher costs are driven by the need to work with the vendors to correct deficiencies that ripple through the CMMC compliance packages. The need for return visits to certify the fixes drives up the cost. Another issue on the assessment front is that a limited number of third-party assessor organizations are available to perform the audit. Getting on their calendar can take months.

The company offering the products to the government also needs to dedicate its personnel to support this compliance activity. In many cases, the company probably needs to add permanent personnel to their staff to manage this process over time.

CMMC compliance is a non-trivial adventure. There are other considerations as well. For much of the newest technology, there are no policies for integrating and deploying new technology into their infrastructure — networks, interconnectivity, communications. For example, the Air Force Space Command is considering using wearable technology to assess Guardian's health assessment. However, there is no Air Force policy or DOD policy on wearables or how to handle the personal health information these devices generate.

The bottom line? It's challenging to get new and innovative technology into the federal government. Even when the federal agencies embrace your technology, there is a significant trade-off for small and medium businesses when they decide to bid on government work. The result? The most innovative companies often pass on selling to the Feds.

AN UPDATE — After we published the newsletter we came across an article from FedScoop that reports that DOD is not meeting the same standards as it expects its contractors to meet. GAO reported that DOD didn’t meet the requirements. GAO also notes that DOD is not legally required to meet the requirements for its own system. (You can’t make this up.) You can read the FedScoop article here.

Licensing Taxpayer-Funded Patents

Lately, the Google article finding machine has been coughing up some interesting posts on patent royalty payments made to government employees. There are many issues regarding how patent licensing and royalty payments are made to federal employees. There is a total lack of transparency on how much royalty money is paid to the federal government and its employees.

The issues surrounding licensing practices go beyond the payments. There are questions on whether there is a conflict of interest when government employees eligible for patent royalties also help their agency or institute select what research they undertake and whom they fund. (Scientific review boards) There are situations where agency personnel sit on standards boards that proliferate through US science and technology policy and statutory and regulatory requirements for technology acquired by the federal government? (DHS's mobile drivers license standards and patents.) Government researchers may have exclusive access to materials and capabilities that academic and corporate researchers don't have. (NIH and DOE)

We came across an article on an expired Department of Health and Human Services patent for using cannabinoid compounds for drug research. The compounds needed to do the research were not available to most researchers in the US because they were considered illegal narcotics. It's not clear if NIH ever received any royalties for the compounds in the patent. But the issue of "early access" to assets needed for research raises important questions on who makes money off of taxpayer-funded research and development.

(We'll leave the exclusive licensing of provisional patent applications that are not in the public domain when an agency issues the license for another day.)

Before We Go

If you aren't a subscriber yet, please consider subscribing. It will help us keep going in 2022. Also, please share FedInvent with other innovation enthusiasts.

Thank you for reading FedInvent.

The FedInvent Team

FedInvent tells the stories of inventors, investigators, and innovators. Wayfinder Digital's FedInvent Project follows the federal innovation ecosphere, taxpayer money, and the inventions it pays for. FedInvent is a work in progress. Please reach out if you have questions or suggestions. You can reach us at info@wayfinder.digital.